Playboy, Kittens, and Deep Learning

It was nearing midnight and it had been a long day, but I was excited. In the morning I had been reading about conv nets, a powerful deep learning technique that lets computers understand images; in the afternoon I had been chatting with one deep learning researcher about how to use them, in the evening I grabbed dinner with a second deep learning researcher, and now approaching bedtime I was tapping away on my laptop marveling at how, in a few lines of code, I could download a vast mathematical structure that could discriminate between a thousand image classes with near-human accuracy. I was messaging an economist friend about how my field was cooler than his because I was so damn excited.

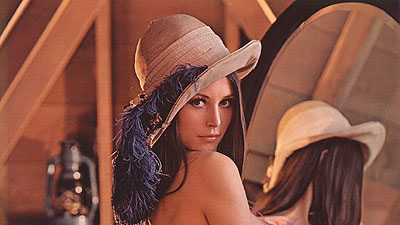

But as I went through the code in a famous deep learning toolbox, I noticed an image file with an odd name – lena.jpg. And with a jolt I realized who she was:

This is one of the most widely used images in computer science. If you’ve ever taken a computer science class that worked with images, there’s a good chance you’ve used it. It also has a lesser-known, controversial history. The image comes from a 1973 Playboy centerfold. It was originally used in a computer science paper because a bunch of USC scientists were writing a paper in a hurry and just needed an image to add as an example, and someone happened to walk in with a Playboy. The image has been widely used ever since then, and there have been complaints for decades that it’s sexist to use it as a standard test image: see Wikipedia’s summary, and also this Washington Post op-ed from a female computer science student at my high school.

While I don’t think this is the biggest deal in the world, I also think it’s pretty obvious that we should stop using this image, for a couple reasons:

- The image has an inappropriate origin. You shouldn’t get your test images from a magazine famous for its images of naked women.

- Separate from origin, the image is obviously sexual. It’s an attractive woman who’s naked from the waist up looking suggestively at the viewer. The titillating nature of the image is clearly part of its appeal: here’s the (male) editor of a computer science journal noting that “it is not surprising that the (mostly male) image processing research community gravitated toward an image that they found attractive”.

- Machine learning already has a problem with oversexualizing women. See Kristian Lum’s piece for some examples, among many others.

- There are literally billions of other images you could use.

To return to my story: some version of the reasoning above flashed through my mind, and my temper flared. It had been a 15-hour day and I had been feeling good and productive and all of a sudden I was not. By midnight, I had stopped writing code and half-written an angry blog post instead. Here is a quote:

“It’s a strange juxtaposition, to see this ugliness in the midst of such beautiful math; to feel walls thrown up around open-source code; to see this tired old image in the midst of such innovation; to feel sudden vulnerability when a second ago you felt invinceable [sic].”

Then I stopped and thought before posting it. The cardinal rule I adhere to when talking publicly about gender issues is don’t do things rashly. As a high schooler, I was a tournament chess player, and I like seeing the battle for gender equality as a chess game – give long thought to every attack, try to look a few steps ahead, keep the end goal in mind. Reflecting on this potential blog post reveals two problems:

- The writing’s a bit sloppy. There’s a misspelling; the parallel structure is a little clumsy; the sentence is a little long. There’s nothing worse than a sentence which strives for eloquence but doesn’t quite achieve it.

- The tone’s a bit harsh. It makes it sound like the person who used the image is severely, perhaps deliberately, harming female computer scientists on multiple levels. To see how this tone was likely to go over, I asked a couple of male computer scientists what they thought about the image. The first man I talked to laughed and said, “people are too sensitive”. The second man also thought the image was fine. Neither had ever heard of its history, and neither was particularly bothered when they did. Now, of course, I write things that others don’t agree with all the time. But their reaction suggested to me that my tone would not persuade most male computer scientists – which is to say, a lot of the people I write for – and would probably actually be counterproductive.

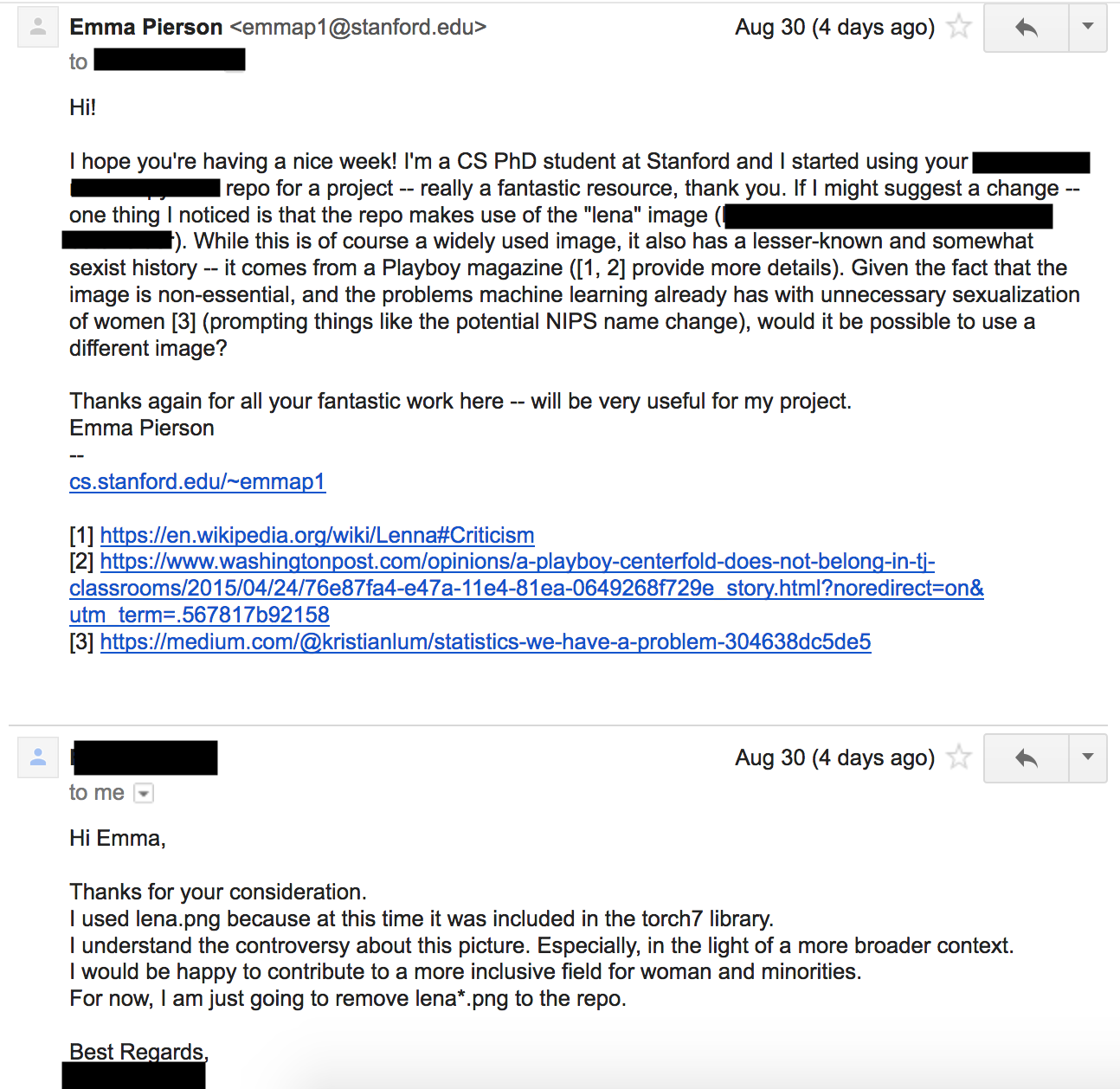

So I went to sleep without doing anything. Over the next few days I reached out to a few people I respected to see what they thought. My anger faded, but I remained convinced the image should be taken down. One option was to open a GitHub issue – essentially, write a public note to the author of the code explaining the history of the image and asking that he use a different one. The upside of this would be to raise awareness of the image’s history and the prevalence of subtle gender bias in computer science, and make it harder for the author to ignore me. The downsides were that it’s a bit pointed to publicly point out sexism in someone’s work; there was also the risk that the whole interaction would end up on the less nice parts of Hacker News or Reddit and waste a lot of my time (although this could also be an upside, if it offered insight into how discussions on these issues evolved). Instead, I decided to privately email the author. If he ignored me, I could escalate by making a public comment. We had the following exchange (I blacked out his identifying details).

Very gracious; totally painless. He was as good as his word: within a day, he replaced the original image with

Thus accomplishing the true goal – to increase the number of kitten pictures in machine learning. Look at its little ears!

As I said at the outset, this obviously isn’t a tremendously momentous interaction. I share it for two reasons. First, women who speak up about gender issues are sometimes told that we should calm down or that we’re being too sensitive, and I wanted to illustrate that we’ve often already put a lot of time into calming down and choosing our words carefully. There’s a good chance that we were actually a lot madder than we’re acting, and it’s probably unhelpful to ask us to calm down further [1].

My second reason for sharing this is that conversations on social justice issues feel so fraught and so frequently blow up, but this interaction gave me hope. When I talk to computer scientists about these issues, I don’t think they are usually as concerned as I am. But I also think that they are at least somewhat concerned and, if you reach out to them calmly and it doesn’t cost them anything, will be receptive to helping you out. Here’s to more kittens and fewer topless women in deep learning.

Notes:

-

Of course, this isn’t always true. Everyone sometimes lashes out without thinking, and some women do this too. But given that most are thoughtful and restrained, I think it’s risky and unfair to assume someone who’s acting angry hasn’t thought about their words. ↩